Opinion Focus

There are some early signs of relief for the supply chain despite a huge amount of hand wringing. The situation remains fragile, with any number of factors likely to rock the boat. Supply chain issues are likely to continue in the medium term.

The world’s food supply chain has been trapped in limbo since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, exacerbated by factors such as high freight costs and bottlenecks, component shortages and the Russia-Ukraine war. Now, some fragile glimmers of hope are beginning to emerge.

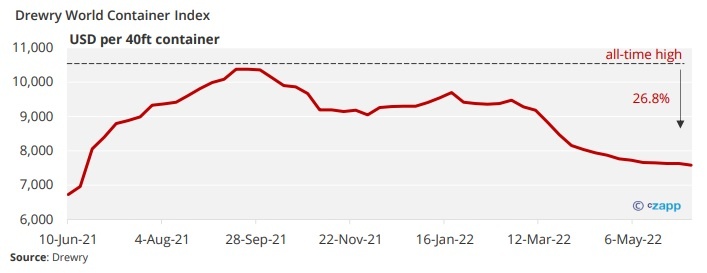

Prices Come Down in Shipping Industry

After over a year of spiralling freight prices, the industry seems to be catching up with demand as rates begin to come down. This month, the Drewry World Container Index was down almost 27% from its September 2021 highs.

The Port of Los Angeles has been experiencing huge backlogs in the past two months, causing inbound container volumes to dip below 2021 levels. Now, it looks like volumes will rebound.

At the same time, average dwell times for trucks and rail links at the port have been coming down. The 30-day average truck dwell time is now 4.6 days, compared with a 5.6-day 90-day average. The rail 30-day average comes in at 7.8 days now, compared with 9 days over the past three months.

2023 is also expected to be the year when large volumes of new container capacity are delivered. According to BIMCO, about 1.5 million TEU of capacity will be delivered in 2023, in addition to the almost 750,000 TEU expected for 2022. This should help the market stabilise further.

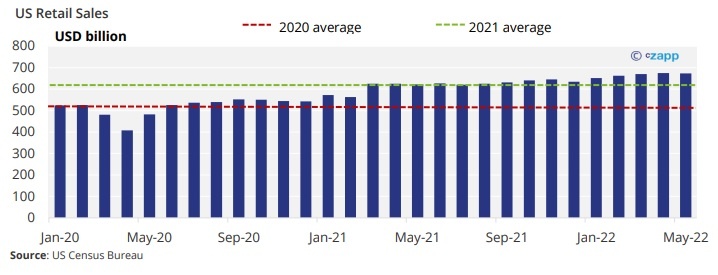

If inflation bites and consumer spending dips, there is likely to be less demand for freight, which would help to alleviate some of the supply snarl-ups. There are some indications that demand is weakening. In its most recent trading statement, UK supermarket Tesco’s CEO Ken Murphy noted “some early indications of changing customer behaviour as a result of the inflationary environment.”

And May US retail figures showed a weakening in retail sales – the first drop in five months. Major retailers Target and Walmart have already cut profit forecasts amid the inflationary environment. However, retail sales remain well above pre-pandemic levels.

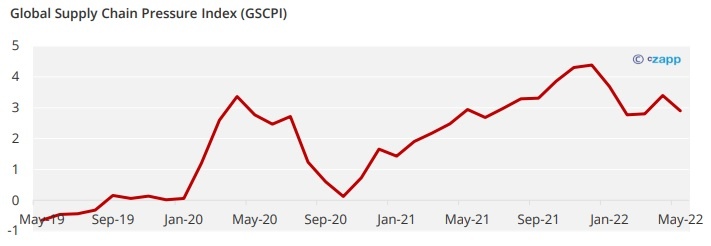

Performance Indices Look Up

The Global Supply Chain Pressure Index – an indicator compiled by the New York Fed to measure supply chain congestion – fell to 2.9 in May from 3.4 in April. The index peaked at 4.4 in December.

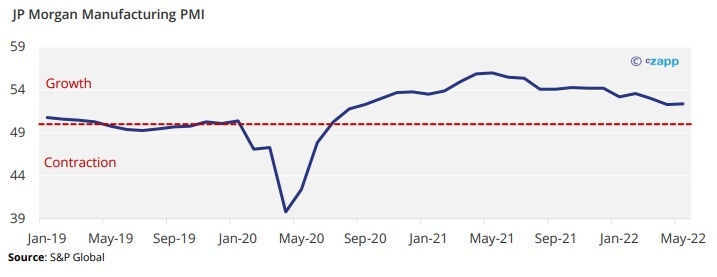

Within the index, factors such as global transportation costs and PMI indicators are brought together to take the temperature of global supply chains. And PMI itself has stabilised into growth territory since July 2020.

While optimism in the index has been dwindling in 2022, it remains above the 50% baseline to indicate a positive rather than negative trend.

This is good news for food machinery firms, who have reported procurement issues and an inability to source key components for machinery.

Global Unemployment Rate Drops

One of the critical components of the supply chain is the global workforce. Most of the major issues – including a rise in freight prices – have been attributed to delays caused by staff shortages.

In this sense, it is good news that the unemployment rate in the OECD fell to 5% in April, down from 5.1% in March and 6.7% in April 2021. This marks the eleventh consecutive month of falling or stable unemployment, which is also now below the rate of 5.3% recorded in February 2020.

While employment rates are high, there is a risk that continued wage growth will fuel inflation. However, a cut in real wage growth would likely stoke negative sentiment, causing widespread strikes.

If there is further wage growth to quell unrest, the supply chain may also feel the brunt of higher payroll expenses.

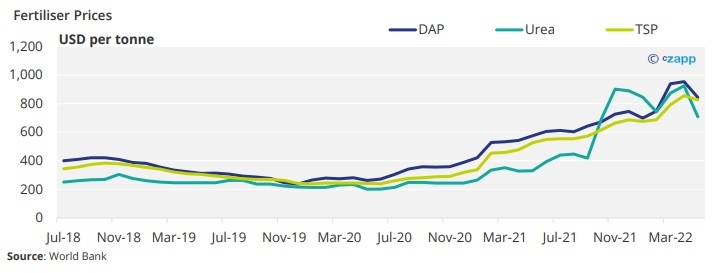

Fertiliser Prices Coming Down

Fertilizer prices are falling back sharply from extremely high levels. The price of urea is now at about USD 707 per tonne, 24% lower than the previous month.

This could be partially due to the reluctance of farmers to buy fertilisers while prices remain so high. Farmers have been using less fertilisers or turning to alternatives to combat price rises.

There is also a glut of fertilisers building up at Brazilian ports, signalling prices may have to come down further. In April, 18 vessels were waiting to unload over half a million tonnes of fertilisers at the Paranaguá port.

Dropping demand and reluctance from buyers to pay current levels is expected to lead to a drop in fertiliser prices in the next few months. However, lack of fertilisers applied to crops will inevitably lead to production losses. Depending on how long the stalemate over prices lasts, this could seriously jeopardise future food supply.

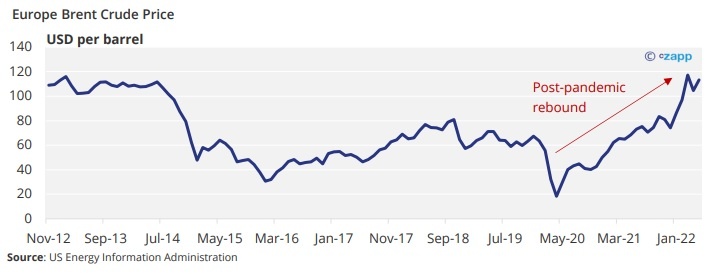

World Oil Markets Begin to Rebalance

World oil demand has steadily increased after pandemic lockdowns and this increase in demand, coupled with supply chain issues, have caused oil prices to skyrocket. This has caused widespread unrest and food insecurity.

Although the Brent crude price remains elevated, energy consumers may soon receive some respite afterOPEC+ pledged to increase oil supply, adding 648,000 barrels a day to production between July and August.

But according to the International Energy Agency, it is non-OPEC+ countries that will lead the world in supply growth in the next year, adding 1.9 million barrels per day in 2022 and 1.8 million barrels per day in 2023.

This could dull the impact of energy price increases, which have been a key driver of rises in consumer purchasing indices. Energy prices have increased by almost 33% in the past year for OECD countries, pulling up the overall inflation rate to 9.2%.

But all eyes will be on Russia. State-owned gas producer Gazprom has already begun to cut off energy supplies to Europe, in particular to Italy and Germany. If Russia also begins to restrict oil supply, prices could rise once again.

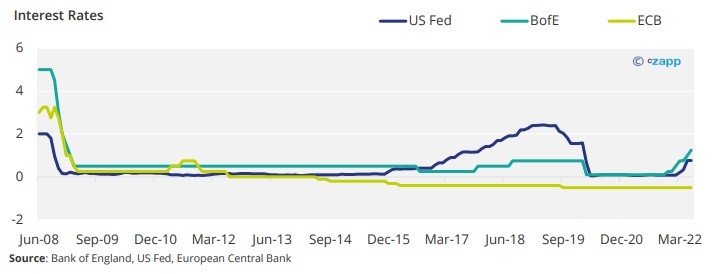

Policy Interventions

Governments and central banks are now keeping a keen eye one inflation and interest rates. The European Central Bank’s main policy interest rate is currently at -0.50% and here have been indications that there will be an imminent rise of 50 basis points or more.

Likewise, US Fed announced a further 75 basis-point rate hike, following on from a 25-basis-point hike in March and a 50-basis-point move in May. The UK’s Bank of England also raised rates from 1% to 1.25% in May – the fifth consecutive hike since December. A shock 50-basis-point rate hike by the Swiss National Bank marked the first rate rise in 15 years, although it remains negative at -0.25%.

But there is a delicate balance that needs to be struck. The supply chain, which depends on credit lines, should expect an increase in costs if rates are hiked again. If the dollar strengthens, this also may be negative for lower-income countries that will see the value of their local currencies dwindle against a strong dollar.

The US is also looking at other ways to reduce pressure on consumers, including evaluation of the tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump in 2018. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said it may lift tariffs on some goods and has already lifted a 25% tariff on the Ukrainian steel sector for one year because of Russia’s invasion.

The WTO published a declaration containing a commitment “to take concrete steps to facilitate trade and improve the functioning and long-term resilience of global markets for food and agriculture.” The organisation said that trade will be facilitated and protectionism minimised to ensure a robust food supply chain.

Concluding Thoughts

- While there are some positive indicators, the supply chain is not yet out of the woods.

- There are some early signs of relief, but this is not the end of the supply chain issues.

- The situation remains tenuous and will continue to be for the rest of the year.

- Any number of factors could mean the situation will get worse before it gets better.

- There is a risk of a self-fuelling inflationary spiral as global strikes create more disruption.

For more articles, insight and price information on all things related related to food and beverages visit Czapp.