Insight Focus

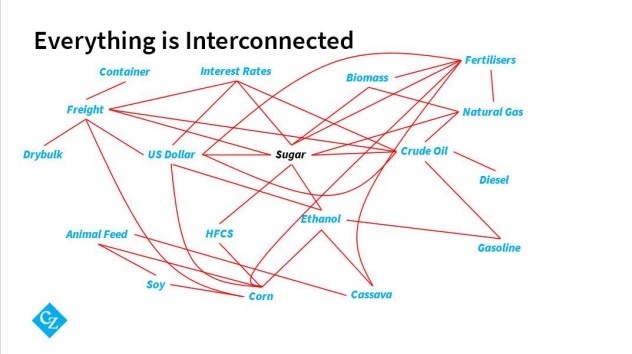

I presented at the S&P Global Sugar Conference in Geneva this week. My talk covered external markets and how they impact sugar. Find out how everything is interconnected.

Alternatively click here to watch Stephen Geldart’s presentation on demand

One of the joys about talking about markets which affect sugar is that I can talk about whatever I’d like. This is because everything is interconnected.

World market sugar futures are priced in US Dollars. Sugar futures contracts are FOB contracts, so we need to think about freight costs. Cane and beet are energy crops as well as food crops. We need to think about power costs, labour costs and competing crop costs. Everything matters for sugar.

Where do you stop? And where do you start?

The US Dollar

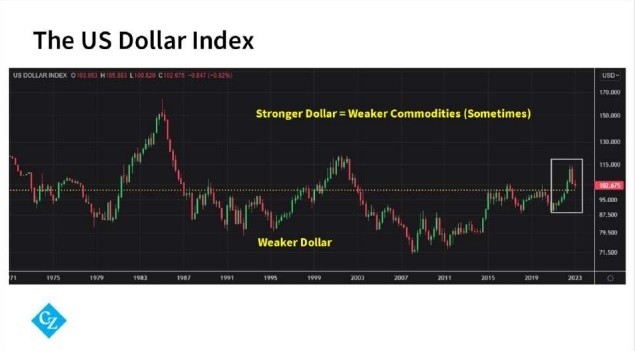

For me, the most important thing for financial markets is the US Dollar. It’s the lifeblood of global trade, most of which is invoiced in Dollars. The Dollar index is a useful tool to tell how strong the Dollar is. It shows the Dollar’s performance against a basket of other currencies, heavily weighted towards the Euro.

It launched in 1973 at 100. When the index rises, it means the Dollar is stronger. When the Dollar is stronger the textbooks will tell you that commodities weaken. Non-American importers can’t afford to buy as much of a good in Dollars and exporters can earn more in home currency. The problem is that the real world isn’t a textbook.

Let’s look at 2020 onwards. You can see from this chart that the Dollar has strengthened, so commodities should have weakened since 2020.

In early 2020 as COVID spread around the world, no-one knew what on earth was going to happen which led to some pretty wild Dollar swings. The Dollar then weakened for the rest of the year. The Federal Reserve was printing a lot of money to keep the American economy going.

Sugar did what the textbooks said it should. Weaker Dollar, stronger sugar. In fact, almost all commodities did this. For example, crude oil almost became worthless then rebounded in May. Copper also bottomed in March.

But in 2021 the US Dollar formed a base and then started to strengthen. Strong dollar, weaker commodities, right? Wrong.

Sugar kept rallying, reaching 20c by October. All commodities did.

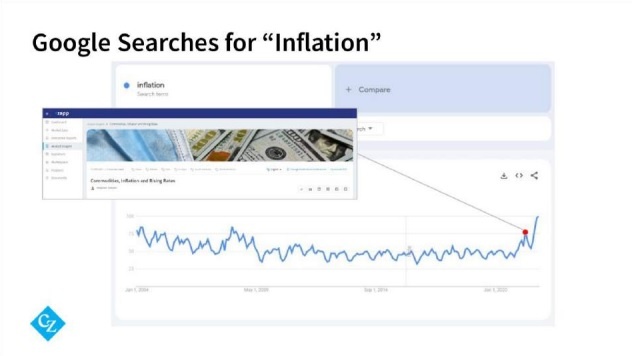

In any relationship between two markets, the market that’s leading often changes. Usually the US Dollar leads everything else. But in 2021 this relationship flipped and commodities led the Dollar higher. The tail wagged the dog, so to speak. For this you can blame inflation.

By the middle of 2021 commodity prices had risen so far that for the first time in decades a few people were starting to worry about inflation.

I first wrote about the risk of inflation in May 2021, for example.

People were betting that the US Federal Reserve would have to start raising interest rates. Stronger rates make a currency more attractive, so the Dollar strengthened.

It took a long time for this to happen, though. The first American rate rise was in March 2022 and Federal Reserve asset buying didn’t reverse until May 2022. By 2022 the Dollar started to accelerate further. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine kept commodities at the forefront of the news, and commodities were leading the Dollar higher still.

It took all of 2022 for the huge rallies in commodities to be tamed by the stronger Dollar and higher interest rates. The uptrends broke as demand for goods slowed and trade became more expensive to finance. Today the Dollar is finally back in control.

Thinking about sugar and the future, what’s fascinating is how resilient commodities have been. The US Dollar rose to levels not seen in 20 years. Interest rates have risen to levels not seen since 2008. Sugar remains at more than double where it was in 2020 and has been strengthening again.

The trouble is that there are often significant time lags between related markets. Sometimes these delays are long, sometimes they are not. Where does that leave us?

The Dollar is trying to stabilize above 100. That’s historically strong. If it succeeds it’s going to be hard for commodity markets to strengthen in the short term. If it fails and weakens further, sugar might find it easier to strengthen more. We’re going to have to watch closely.

Natural Gas

Let’s look next at energy.

Energy security is national security. Without a cheap and stable energy supply, you don’t have refrigeration, you don’t have truck, rail or air supply chains, and you don’t have heating or air conditioning.

This should be easy to understand. But sadly, it seems that politicians across Europe haven’t understood how important energy policy is, nor that all markets are interlinked. This is especially true in the UK.

This year we ran out of tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers thanks to poor energy policy. If you went to the shops in February you couldn’t buy them. The shelves were empty. Everyone blamed the weather. In the winter, warmer countries like Spain and Morocco supply a lot of the UK’s salad vegetables and bad weather hit yields. But the reason weather could have such aa big effect on supply was due to energy.

Most salad vegetables in the UK are grown in large greenhouses. Here’s one that’s just outside London. It’s around 300m by 300m, to give you an idea of scale.

It takes energy to heat these greenhouses, to keep the light and humidity levels right and to pipe carbon dioxide into the greenhouses to promote photosynthesis. Almost all of this energy comes from natural gas.

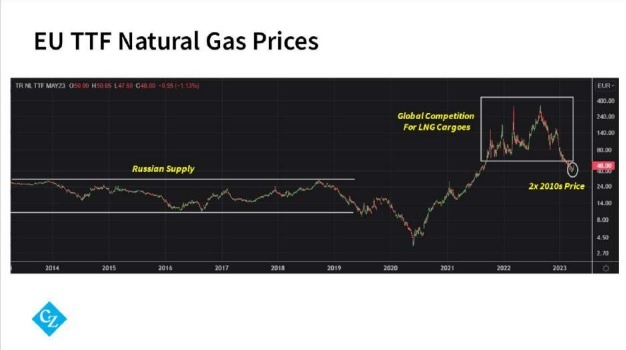

For years natural gas prices in the UK have been low. We had North Sea supplies, then Europe had cheap Russian supply. The European natural gas price through the 2010s was between 10-30 Euros per megawatt hour.

Politicians assumed natural gas was natural gas – the same molecule at the same price whether it came from the North Sea, Russia or Qatar. It could all be delivered cheaply on a just-in-time basis. Indeed, the UK shut 70% of its gas storage in 2017. The government thought it was too expensive to operate. Sadly, we all know what happened next.

Global demand for energy increased as we learned to live with COVID. Prices increased. In 2022 Russia invaded Ukraine, gas flows to Europe stopped and prices went through the roof, peaking at 10 times the 2010s range.

Although energy prices rose, UK supermarkets refused to offer UK greenhouse operators higher prices for their crops, and so farmers chose not to grow salad vegetables. Imports were then hit by bad weather and there were no tomatoes in the shops.

Now, the UK government probably won’t be overthrown because people can’t eat their vegetables. But many other governments are far more sensitive than British politicians to food security. Most important of all for the sugar market is China.

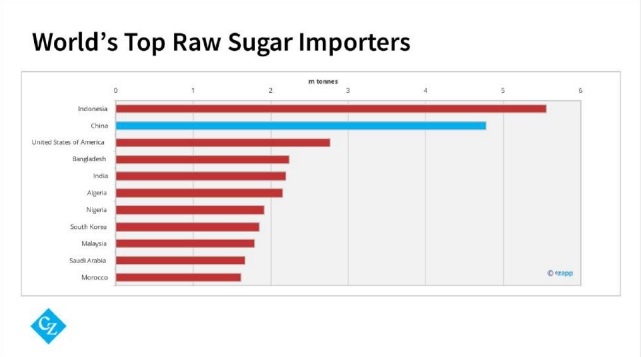

China is usually the world’s largest sugar importer, accounting for roughly 4m tonnes of raws and another 2m tonnes of other sugars.

Older people there can still remember hunger from the three years of famine in the early 1960s.

China has held large sugar stocks for years, for long enough in fact that no-one quite knows the size of the stockpile. We think there could be around 6m tonnes of sugar in stock.

When local sugar prices are high, as they are today, the Chinese government can release stocks. They did this during the last major bull market in 2009-2011 for example.

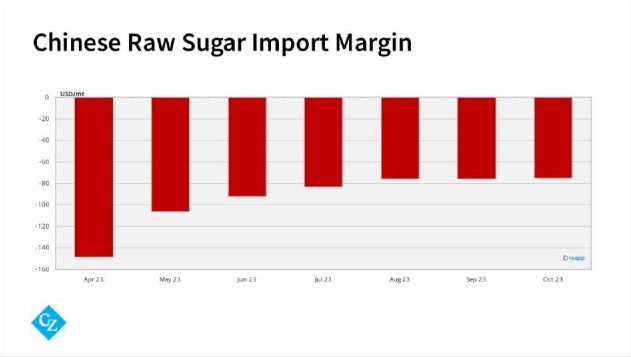

Today Chinese out of quota sugar import margins are negative. The government also doesn’t want local sugar prices to rise further. It called a meeting 2 weeks ago to warn the industry about high prices. Much of the Chinese industry is operated by state-owned enterprises and the private sector are dependent on the government for licences to operate and import. The government can find ways to manage the market. They care about food security, and the costs to maintain it in sugar and other goods are trivial compared to the cost of civil unrest.

We’ve seen similar attitudes in other countries too. Look at Algeria and Egypt.

Both homes to major sugar refiners who in normal times would import raw sugar for processing into white sugar for export.

Today both countries have banned sugar exports. Even those refiners which are allowed to operate: those in Dubai, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Bahrain, India and so on are struggling with higher energy costs.

Natural gas prices used to be regionalized. Gas could only be moved long-distance by pipeline. Today liquified natural gas means that there is a more effective world market price.

The EU TTF price no longer just reflects supply from North Sea gas fields, nor supply from Russian pipelines. In the past winter it’s shown the price of LNG cargoes arriving from the US or from Qatar. Europe competes with China, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Egypt and many others for these cargoes.

Russian supply can’t yet be liquified for LNG export nor piped east at scale. I’d expect the world’s natural gas prices to remain above the 2010s level for a few years to come.

Today natural gas prices are around double the 2010s average, at 40-60 euros per megawatt hour. This is important. Many of the world’s re-export refiners are paying higher energy costs than they used to. These refiners are the flexible suppliers to the refined sugar market. The cost of this flexibility has increased,meaning the white premium, the difference between refined sugar futures and raw sugar futures, has also increased.

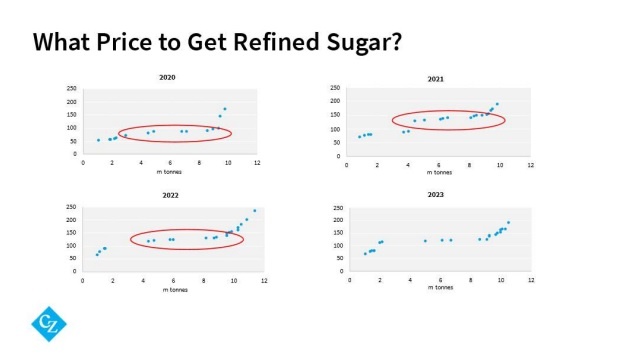

Here’s our model for how much it costs to add to the world’s refined sugar supply.

The x-axis on the plot shows how much more refined sugar can be supplied to the world market at a given price over the raw sugar futures. Each dot represents a supplier and the price at which their sugar becomes available, in US Dollars per tonne.

You can see the price at which you start to introduce a lot more flexible supply into the market, from toll refiners. In 2020 most supply coming to market was around $80-100. The white sugar premium – the difference between refined futures and raw sugar futures, was a little below this level for most of the year

In 2021 most commodities were stronger, including energy costs and freight costs. To get that flexible supply the price is closer to $130-150/mt. By 2022 we have a full-on energy crisis. This was when natural gas peaked at 10x normal levels in Europe. Compare to 2020. In 2020 $80/mt got you more than 8m tonnes of refined supply from a diverse range of suppliers. In 2022 it got you less than 2m tonnes from a handful of cane processors. To get 8m tonnes of supply still takes around $130/mt. But there’s also a large cluster of suppliers at more than $150/mt.

Today energy and freight prices have calmed down but we’re still nowhere near as cheap as we were before natural gas prices went nuts. As long as the refined sugar market remains undersupplied and natural gas prices remain high, the white premium will remain high too.

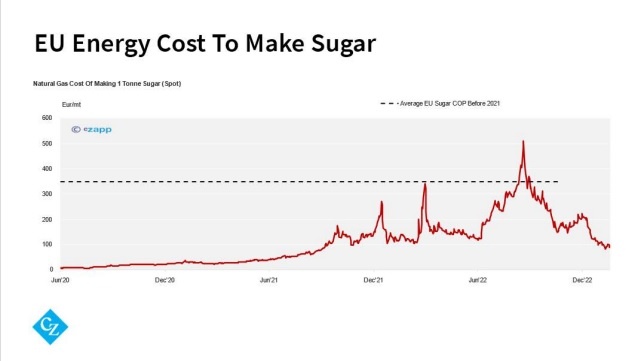

Speaking of refined production, let’s look at European beet processors. Higher gas prices also make European beet processing more expensive. In the mid-2010s I used to consider western Europe to be the world’s cheapest supplier of high quality refined sugar. This isn’t true any longer.

At one point at the end of last year we calculated European beet processors were paying as much for energy to make a tonne of sugar as they used to pay for the entire production process. If gas prices remain where they are today it’s hard to see how European exports can be competitive versus cane-derived refined sugar.

Fertilizer

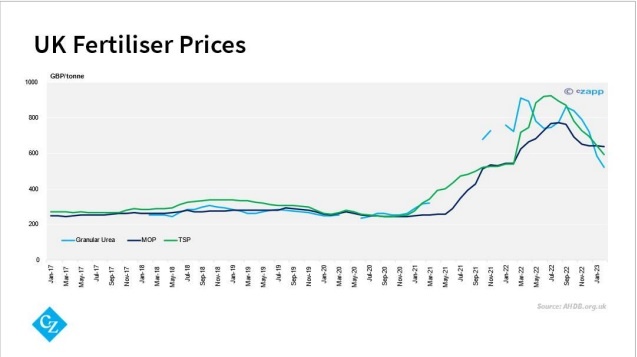

Another industry which has been hit hard by the rise in natural gas prices is the European fertilizer industry.Making fertilizer is extremely energy intensive, especially nitrogen-based fertilizer. To convert nitrogen to ammonia requires high temperature and pressure and metal catalysts. This means that some of Europe’s fertilizer industry stopped operating in 2022.

Even today it won’t be as economically viable as it was. Fertiliser prices remain high, even if they’re falling from last year’s peaks. Here’s a chart of UK fertilizer prices showing the state of play today.

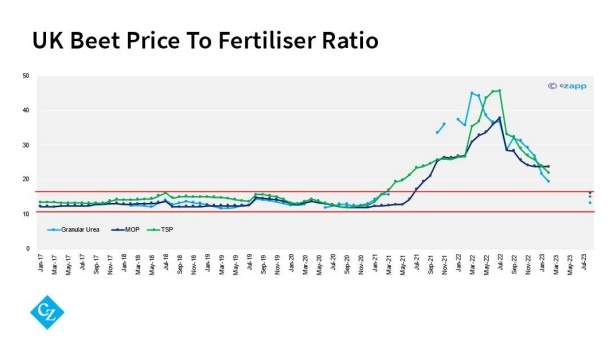

Like most commodities, prices have started to fall but remain far above where they were in the 2010s. What does this mean for farmers? Here is the fertiliser price to beet price ratio, using the UK processors annual beet price.

This year UK farmers have been offered £40 per tonne for beet, up from £27 last season. Those who are using Czapp’s beet pricing tool have been able to capture more than £50 per tonne for their beet recently.

The high beet prices mean that fertilizer is as affordable today as it was in the 2010s for farmers.

This is good news for farmers, clearly, and should help beet yields this year too. But consumers won’t see the benefit. Higher beet prices mean higher costs to make sugar. Sugar prices won’t go back to 2020 levels even if energy prices do; not until beet prices have fallen too.It’s not just Europe that’s struggling with fertiliser.

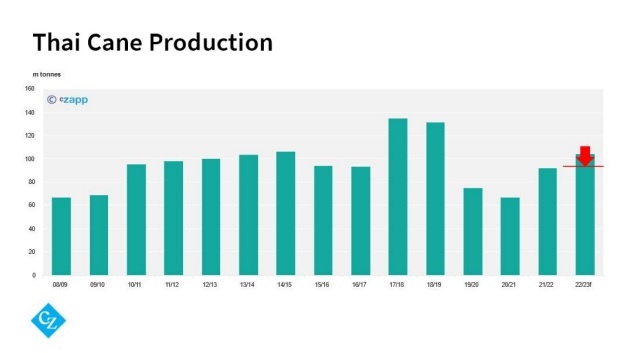

In Thailand mills this year were expecting more than 100m tonnes of cane to be harvested. The actual figure was around 94m tonnes of cane. We think productivity was low in part because farmers chose to apply less fertilizer or chose cheaper, less high-quality fertilizer mixes, for example.

The rise in the price of energy has another major implication for many of the world’s cane mills.

Biomass

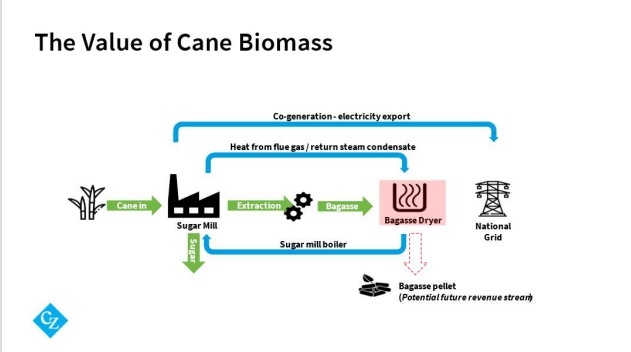

It’s made their bagasse far more valuable.

Cane mills have long used bagasse to power boilers: using a waste product to make energy. Today, mills can upgrade to high pressure boilers to use less bagasse and sell the surplus. If no local mills can buy the bagasse, it can be exported; European power generators are hungry for sources of biomass to replace coal-fired generation. A mill could also invest further in bagasse drying facilities to further concentrate the energy intensity of the fuel, or indeed build a pellet plant for exportsThe rise in the price of energy has another major implication for many of the world’s cane mills.

In an era of high energy prices, cane mills can finally capture significant value not just from the sucrose in the cane plant, but also from the fibre of the cane plant.

Cz are active in this area. We finance new mill investments in boilers and biomass. We buy and ship and sell biomass globally. We optimize biomass supply chains. We’ve done several consulting projects to help people across the whole biomass supply chain. Please talk to me if you’d like more help.

Crude Oil & Ethanol

Let’s now look at crude oil and gasoline. Cane and beet are food crops, but also energy crops, with cane being used to make ethanol in Brazil and now also India. In both countries government regulation around the fuel markets makes the relationship between sugar, ethanol and gasoline complicated.

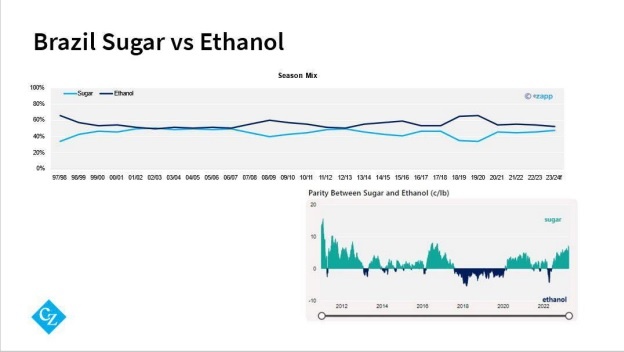

In general, if crude oil prices are higher, so are gasoline prices and this means that drivers prefer ethanol, leading to more ethanol demand. In Brazil, this can mean mills make more ethanol and less sugar, which could be positive for sugar prices.

But we’ve seen in 2022 how governments don’t like fuel price inflation and can regulate it away, meaning the crude oil to sugar relationship breaks down.

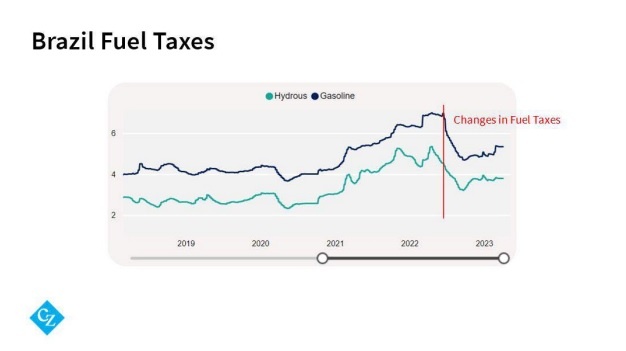

In Brazil, gasoline prices approached 7 Reais per litre in the middle of 2022. This was causing serious hardship and so the government changed fuel taxes to bring prices down at the pumps. You can see how prices fell in the months that followed.

This meant that ethanol prices also fell so that it could remain competitive. This in turn meant that sugar became a much better paying product for mills. Mills maximized sugar output even though energy prices were high.

Mills now make 6c/lb more by making sugar than they do ethanol, even though the tax changes have now been unwound. Taxes could be re-applied if prices go too high too quickly.

We also need to bear in mind that Petrobas keep local gasoline prices roughly aligned with international markets, but this may not continue in the future. We have a PT government headed by President Lula now, and when PT were in power previously they restricted gasoline prices.

The relationship is less clear still in India, where the government controls all aspects of the cane economy and much of the fuel market too.

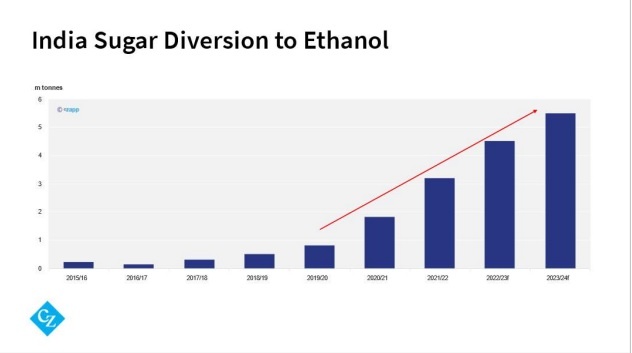

One interesting thing here is that India’s programme to reach a 20% blend of ethanol in gasoline by 2025 was initially introduced as a way to soak up excess sugar rather than subsidizing its export, which was being challenged at the World Trade Organisation. For some reason subsidizing fuel supply is internationally

acceptable but subsidizing food isn’t.

But since the 2020s the government now believes the move to E20 is a key part of its energy security strategy and reducing excess sucrose is no longer the main aim of the programme.

So India might be about to trigger a new bull market in sugar thanks to high crude oil prices, by removing all of the cheap excess sugar that’s flooded the world market during the 2010s. Bear in mind that E20 by 2025 will probably mean diverting around 6m tonnes of sugar to make ethanol, but Indian gasoline demand is growing at 7% a year. By 2035 12m tonnes of sugar will need to be diverted if that growth rate stays the same.

Sugar’s Problems

This is really important because the world can’t really afford to lose sugar production today. Global sugar production has stagnated at around 175m tonnes a year, plus or minus 15m tonnes, for more than a decade.

Since the Brazilian cane sector almost went bankrupt after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, we’ve barely seen any investment in sugar production around the world. Sugar prices fell from 36c in 2011 to 9c in 2020. Of course no-one invested when prices fell for that decade. It’s a similar story across most commodities.

This is a problem today because sugar consumption has finally caught up with production, it’s going to exceed 175m tonnes this year.

So in good years, we’ll make enough sugar to meet consumption. In bad years we won’t. For example, this year we’ve not made enough sugar to meet consumption.

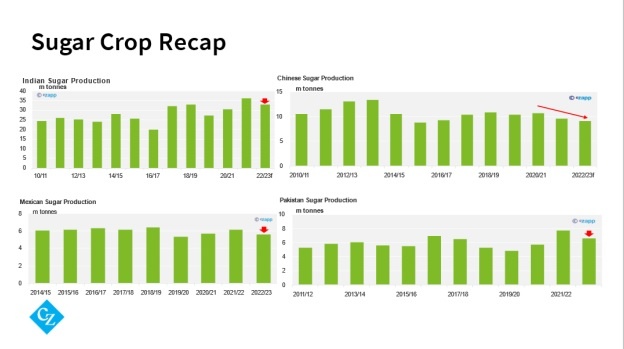

Cane crops in 2023 have been poor. I’ve already mentioned Thailand, but India’s crop is also not performing as well as hoped. Neither has China’s, nor Mexico’s, nor Pakistan’s.

These countries are all major cane growers. Is it any wonder sugar prices are strong again? We’ve reached the stage where the world can’t accommodate crop failure for a major sugar producer. Short term supply problems are being reflected in the price.

The problem here is how to encourage investors back into sugar cane and beet growing and processing. This is happening in India only, thanks to government support for ethanol production.

Building a cane mill is capital intensive and takes time. It also takes time for cane fields to be prepared, planted and mature.

In Brazil, the cost of sugar production is very approximately 16c/lb, if I can summarize nearly 300 mills with one number. Investors will want a return above this level and for this return to be sustained for as long as possible.

I mentioned rising interest rates right at the start of this presentation, so perhaps it shows how far everything is connected that I can talk about them at the end too. The SELIC benchmark interest rate in Brazil today is close to 14%. If investors require a premium to this to reflect the risks associated with building cane mills in the country, then raw sugar futures prices really need to sustain above 20c/lb.

In recent months the futures curve has been rising. The front of the curve gives the right signal; the back of the curve remains too cheap on this analysis.

Managing Price Risk

I hope if you remember one thing from this presentation it’s not the details about growing tomatoes in greenhouses near London nor how difficult it is to make ammonia. I hope you’d appreciate how complicated even our little sugar world is, how everything is interconnected.

You never quite know for certain which market is leading which, nor when this leadership changes. So how do you cope with this degree of chaos when making decisions for your business?

One thing is to be aware of different time frames. It’s perfectly ok to be worried that sugar might weaken in the short term and be extremely bullish in the longer term.

Another thing is to simplify your news intake. Most of what you see in the news doesn’t matter much for prices. Bloomberg and Reuters and CNBC will make a massive deal about CPI and PMI and other indicators, but they’re almost always irrelevant. If you spend your life watching indicators and the news you’ll miss what’s really important.

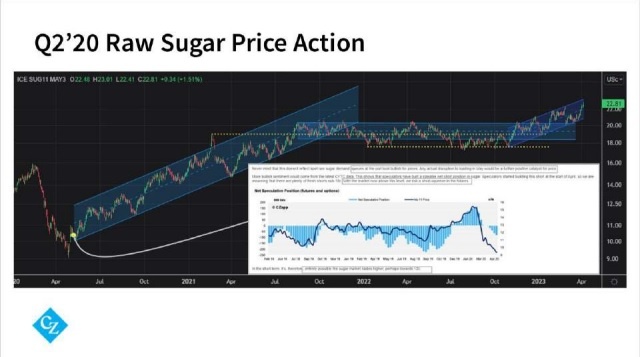

In Q2’20 all economic indicators were awful yet the commodity markets were about to go on a major bull run.

Price itself can tell you a lot. The sugar market was shorted heavily by speculators, but once it hit 9c someone bought aggressively and trapped new shorts. I didn’t know who had bought (it turned out to have been Chinese refiners), but I knew as a result in early May that the sugar market was about to strengthen: I told all of my customers and subscribers I thought a 20% move to 12c was possible!

Likewise just before Russia invaded Ukraine I suspected the move higher in commodities was getting stale. In markets, timing is everything and I got the timing wrong here; I even said at the time I was probably too early. But a month after the invasion it was clear that crude oil had exhausted its uptrend.

As my wife reminds me, no-one’s perfect. If I could get this exactly right I wouldn’t be here with you right now. I’d be on the beach full-time.

Part of the skill in analysing other markets is knowing when to stop. And with that, I shall. Thank you

For more articles, insight and price information on all things related related to food and beverages visit Czapp.