Opinion Focus

Carbon labelling has become a key trend in the food and beverage industries. There is still uncertainty over the accuracy, cost and effectiveness of carbon labels. The future agenda is likely to be driven by food producers and regulators rather than consumers.

Carbon labelling has been big news in recent months. As a range of entertainment venues from restaurants to arenas adopt the practice, there is uncertainty over what carbon labelling actually measures. Now, as the cost-of-living crisis heats up, will food retailers and supermarkets shun additional climate commitments in favour of keeping costs low?

Carbon Labelling Gathers Momentum

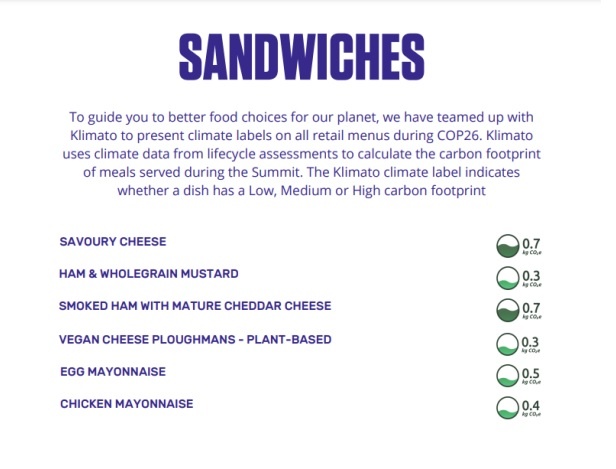

Carbon labelling has become increasingly popular with companies, particularly in industrialised countries. One of the biggest events for carbon labelling came in the form of COP26, held in Glasgow, Scotland last year. During the conference, menus listed the carbon footprint of all meals on offer.

The event organisers partnered with Swedish start-up Klimato to analyse carbon footprints and printed the results in an initiative known as A Recipe for Change.

Source: A Recipe for Change

Over 2022, the movement has gathered steam. In April, Boston university campus UMass Amherst announced it would include carbon labels on all its menu items. In the UK, the menu for popular music’s BRIT Awards was curated by Levy UK+I, which incorporated carbon labelling. The company is now working with the O2 Arena in London, which welcomes 9 million visitors a year.

The movement has also penetrated the catering space. French food services firm Sodexo is currently trialling a carbon-labelled menu, while some independent restaurants in the UK have launched their own initiatives.

Certification Criteria Vary

UK vegan charity Viva! Is calling for carbon labelling to be made mandatory in the same way that calorie labelling is now required on most food packages. But how does carbon labelling actually work? And how are the calculations quantified?

Well, there are many different carbon labelling efforts out there. In addition to Klimato, companies such as CarbonCloud, VCS, Gold Standard, Kafoodle, Carbon Trust and ClimatePartner all have their own methodologies for measuring CO2 emissions.

Under some circumstances, carbon offsets are can help companies obtain more favourable carbon labelling. This is particularly true for companies that cannot reduce emissions in a certain part of the supply chain — for example, a Norwegian coffee shop that must source its beans from South America. This is often done through a system of credits.

While ClimatePartner and Carbon Trust consider carbon offsetting to offer climate neutral certifications, CarbonCloud does not include these calculations. CEO David Bryngelsson told Czapp that this is because “it does not solve the actual problem and tends to misdirect efforts in the wrong way.” He argues that carbon offsetting often leads to a lack of transparency and double-counting of the offset emissions.

Carbon labelling companies all say they track carbon emissions on food products from the agricultural phase through to the supermarket shelf, but methodologies vary. Some companies use life-cycle assessments, while others stick to Public Available Standard 2060. They can also choose from the Greenhouse Gas Protocol and International Organization for Standardization 14067. Some use a combination.

Carbon Trust requires data for 12 consecutive months and any supply chain issues within that period are taken into account during the footprint and certification. For CarbonCloud, details within transport such as increased idling times due to congestion are not included but probably will be in future

Accuracy Matters Less than Awareness

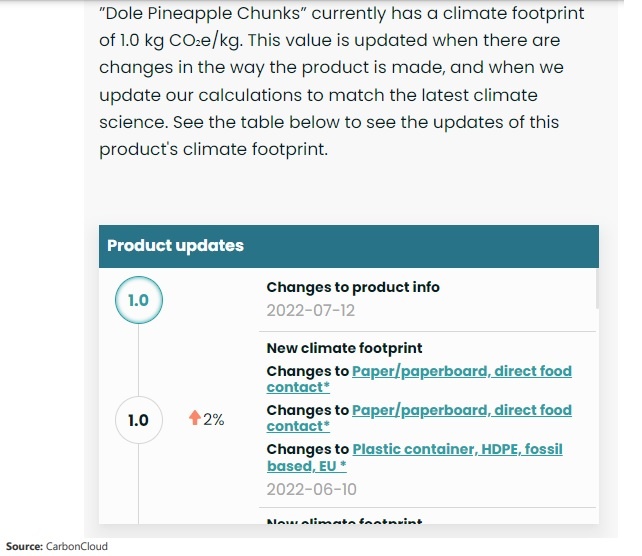

All this means there are differences in how carbon emissions are measured from company to company and the measurements are constantly evolving. On CarbonCloud’s website, changes are regularly made to footprints to reflect changes in packaging materials, changes in manufacturing processes and changes to calculations based on the most recent scientific evidence.

But even with all these measures, it is almost impossible to deduce the exact carbon footprint of a given product. But for Bryngelsson, this is not really what is important. “No one taking climate change seriously thinks that labels will solve the problem, regardless of how pretty or rich in information they are,” he says. “That is not why we help food producers climate-label their products.”

The real purpose of carbon labels, he says, is to make food producers aware of the carbon impacts at each stage of their supply chain so they can address these leakages.

Carbon Trust Associate Director Silvana Centty echoes this sentiment. “Product footprints help clients understand where their emissions come from, and as a result, we have seen many surprises over the years,” she said. “This underlines the importance of the process by providing facts and data which clarify preconceptions and help organisations tackle emissions.”

Trends Follow the Money

So, what motivates companies to invest in carbon labelling? Contrary what they may want you to believe, it’s not all about doing good. There is big money in ESG (environmental, social, governance).

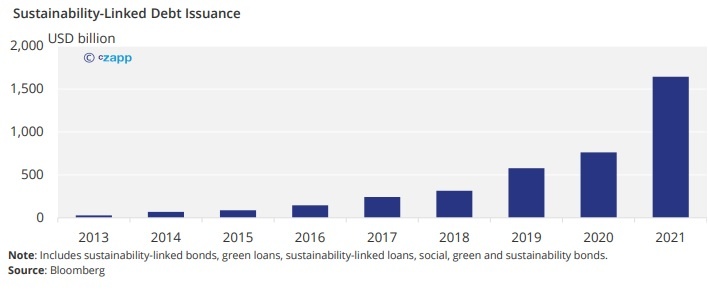

According to financial intelligence provider Morningstar, the global asset management industry earned USD 1.8 billion in fees from their sustainable funds in 2021, up from about USD 1.1 billion in 2020. Sustainability-linked debt issuance has also soared since 2013.

ESG-linked bonds can command lower interest rates, meaning they are attractive to borrowers. But this also comes with a catch. Strict parameters are imposed on borrowers, requiring certain ESG-related commitments to be fulfilled. This can include reducing CO2 emissions, hitting recycled materials targets or developing new environmentally friendly technology.

The targets are sure to become stricter. Recently, major banks have been accused by the US SEC of “greenwashing” financial products to market them as more sustainable than they really are. One German asset manager was subject to a police raid, setting the example that financial products marketed as sustainable must be demonstrably so. This new scrutiny means Investors are now likely to hold companies to higher ESG standards than ever before.

It is likely that the adoption of carbon labelling practices will be accelerated by regulatory requirements, Bryngelsson said. “From the food producers and vendors perspective, [carbon labelling] is increasingly being driven by looming regulations as the ambitions for fighting climate change are not pausing.”

Companies are also attracted to the prospect of obtaining higher levels of customer loyalty by broadcasting their ESG credentials. According to a 2021 report by PwC, consumers are rewarding business for ESG performance. About 80% of those surveyed by the consulting firm said they were more likely to buy from a company with a strong track record on environmental and governance matters.

Price Pressure Could Impact Momentum

Consumers are likely to buy from companies with solid ESG credentials. “Our latest consumer research indicates 67% of respondents liked the idea of product footprint labelling and felt more positive towards companies reducing the footprint of their products,” Centty said.

But are they willing to pay more for these products? The carbon labelling process is time-consuming and costly, and consumers may find themselves shouldering some of the cost burden. “Currently we are not seeing an impact [from the cost-of-living crisis]; but it’ still too early for us to comment,” Centty added.

Even retailers may be reluctant to take on these additional costs. In 2007, for example, UK supermarket chain Tesco announced a plan to carbon label all its products. But the supermarket dropped the plan five years later due to the extensive work and cost involved.

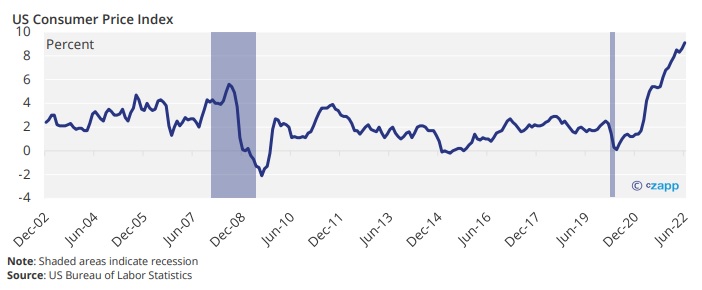

Already, inflation is at its highest level in at least 20 years at 9.1% in the US in June. Despite several interest rate hikes in 2022, economists fear inflation could continue, buoyed by energy costs caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In a study by EY about the adoption of clean energies, the consultancy found that, while consumers are open to alternative energy options, cost is the top priority. A Deloitte study found that 52% of UK adults say a sustainable lifestyle is too expensive. This sentiment is likely to be echoed for food choices.

Concluding Thoughts

- Carbon labelling does make us consider what we are purchasing.

- The process and methodologies are still constantly evolving.

- Truly accurate and authentic labelling is likely still a way away.

- Even if it’s not exact, it can give companies an idea of where to target emissions reduction efforts.

- Although ESG concerns are top of mind for consumers, these are likely to be overridden by living costs.

- Carbon labelling will be driven more by the supply side than the demand side over the next few years.

- But investors and governments will likely continue to require strict ESG criteria, creating greater momentum for carbon labelling.

For more articles, insight and price information on all things related related to food and beverages visit Czapp.