Insight Focus

The sugar market has rebounded thanks to fears of El Nino. This can cause dry weather and poor cane growth in the Western Pacific. But El Nino’s impact on the sugar market is complicated.

Click here to watch on demand!

Hi everyone, it’s Stephen here with a sugar market update for May 2023.

I know, it’s mid-June. Apologies for being late but I’ve been travelling quite a bit, so I’ve not had a huge amount of time to sit down and prepare some thoughts for you.

One thing I’ve been saying in recent weeks is how the sugar market has run out of buyers.

Specs have been long since around November last year. The trade have been long since early this year, at least around the time of the Dubai sugar conference in late February. By the time of the Geneva sugar conference in April the trade had managed to whip up panic among sugar consumers by saying that El Nino was possible this year, driving prices up to 27c.

With everyone long and no pressure on producer short hedges, I’d assumed that we’d run out of buyers and so prices should drift to the low 20c area. I still think that’s possible, but my thesis got a bit of a workout at the end of last week.

On Thursday the American Climate Prediction Center officially confirmed there’ll be an El Nino weather event this year. This drove more buying interest in sugar while Brazil was on holiday so there was very little overhead selling.

Seeing as the market is so jumpy about El Nino, let’s look at what this means in a bit more detail. So the first problem is that when it comes to the weather, nothing’s very clear-cut. Trust me on this, I’m English. We often get 4 different seasons in just one day and can talk about the weather for hours.

The Americans look at sea surface temperatures and the tropical pacific atmosphere to determine if an El Nino is occurring. They think we will have an El Nino.

Australia looks at trade winds, the southern oscillation index, weather models and sea surface temperatures. According to their method, we’re on El Nino alert, but they’ve not declared an El Nino yet.

Japan declares an El Niño when the 5 month average sea surface temperature deviation is more than 0.5 degrees warmer for 6 consecutive months.

Even when an El Nino is declared, there are different types. An El Nino occurs when a band of warm water develops in the Central and East-central equatorial pacific ocean accompanied by low air pressure in the eastern pacific and high pressure in the western pacific.

There’s the vanilla Eastern pacific El Nino.

But there’s also a central pacific El Nino, called a Modoki El Nino. Modoki is Japanese for pseudo, so a Modoki El Nino is a pseudo El Nino; similar but different.

During an El Nino event, the area of warming can change, so a regular El Nino can morph into a Modoki and reverse again. Weather systems are dynamic, not static.

The duration of an El Nino can also vary. They generally last for 2 years, but this isn’t a solid rule. This is important for us because sugar cane has long growing seasons. A short El Nino may have less impact on cane development than a longer one. The effect of an El Nino can also depend on the time of year it forms.

So far so messy. Let’s look at the what average El Ninos can do to the weather.

In general, very broadly, an El Nino leads to less rainfall in the Western Pacific as the warm water spreads from there into the East Pacific, taking the rain with it. This can mean dry conditions in India, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and northern Australia, all major sugar cane growing regions. This is something to watch out for in the next few months, especially for northern hemisphere regions where cane is growing.

The excess rainfall instead appears in the Eastern Pacific, meaning that southern Brazil and northern Argentina can be wetter than normal in the middle of the year. This has the potential to interfere with cane crushing progress, which could be a problem in Centre-South Brazil, the world’s largest cane region where mills are already in a race against time to harvest all available cane this year. On the plus side, higher than normal rainfall this year might mean better quality cane next year.

Further away the weather effects become more speculative and harder to pick apart, but it’s possible that southern Africa has a drier than normal Q1 while East Africa might be wetter than normal. It’s worth highlighting again that these are general conditions El Nino brings, but there’s no guarantee that any of these things happen, nor that they are sustained. It depends on the type, intensity and duration of the El Nino event.

El Nino also isn’t the only determinant of weather. As the US CPC says, you can’t blame it all on El Nino.

One study found ENSO was only the cause of around 20% of extreme precipitation with the remaining 80% coming from other factors. Weather is chaotic; no single El Nino will match the ideal or average El Nino.Don’t forget also that cane can be a durable crop. It’s a type of grass and so is pretty robust.

It does need a high amount of rainfall during its growth phase, which is starting around now in the northern hemisphere, but that rainfall can be sporadic without causing too much stress on the plant. Is it any wonder

that the national Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration once referred to El Nino as an unreliable bartender? One that doesn’t always give you what you ordered?

With all this in mind, let’s look at other recent El Ninos.

In my sugar career there have been three, a major event in 2014 to 2016, and weaker ones in 2009/10 and 2018/19.

Let’s look at the big one first, which was both a Modoki El Nino and a regular El Nino.

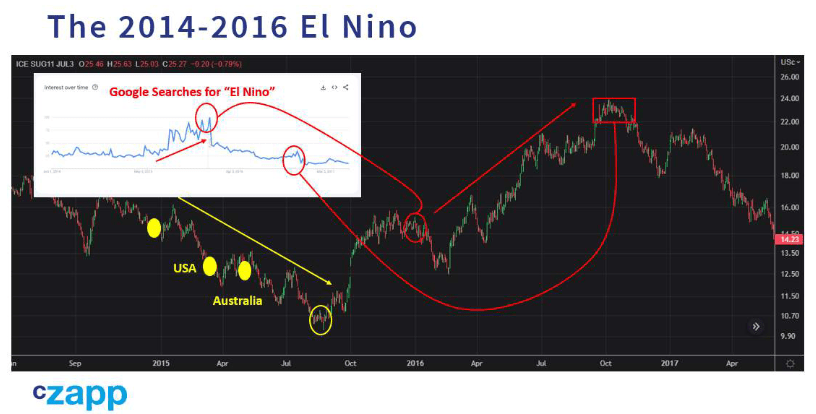

The first to declare an El Nino were Japan and Hong Kong at the end of 2014. The USA followed in March 2015, then Australia in May 2015. Through this time, raw sugar was still collapsing from its 36c highs in 2011, and wouldn’t reach a bottom of 10c until August. By around this time it was clear that the El Nino would intensify into strong conditions by the end of the year.

Prices bottomed just as this newsflow was most intense. Google searches for El Nino picked up in June 2015 and peaked in the first week of January 2016. By this time prices had moved more than 50% from the lows, towards 16c.

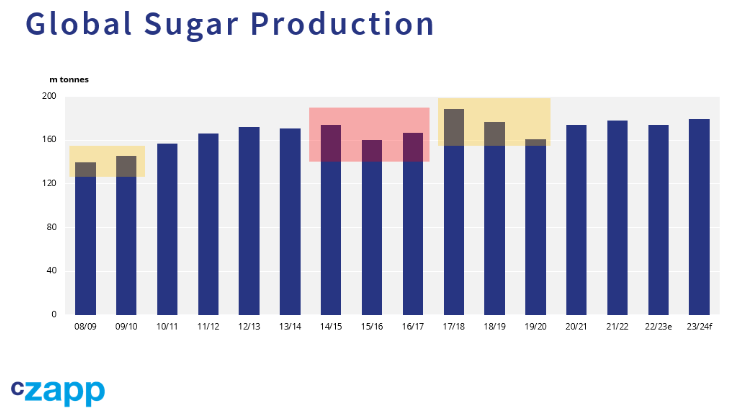

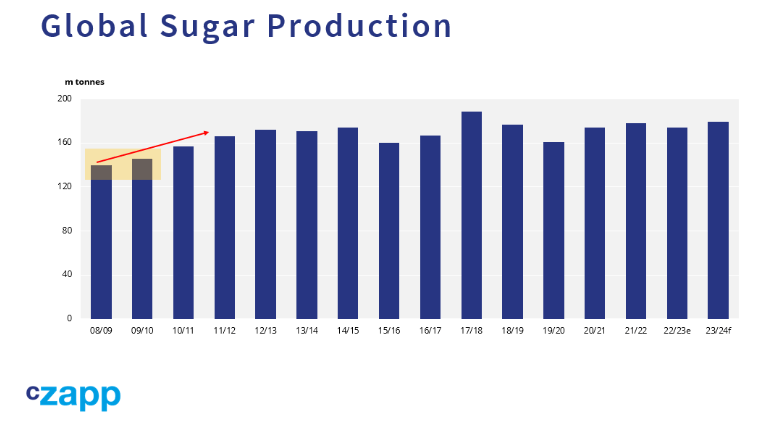

Global sugar production fell from 174m tonnes in 2014/15 to 160m tonnes in 2015/16 and 167m tonnes in 2016/17. This means the peak fall in production was 14m tonnes. However, many major regions were unaffected in 2015/16, places like Brazil, India, and Australia.

Much of the losses seems to have come from more minor sugar producers and so may not have been directly linked to El Nino. The impact on India was only felt in 2016/17, by which time production had fallen by 8m tonnes from its 2014/15 peak.

Meanwhile, although interest in El Nino peaked in December 2015, prices only peaked in September 2016, at 24c, a level we’ve only just recently regained. By this time most non-commodity people had forgotten all about El Nino.

As I said earlier, El Ninos are unreliable indicators. Just because the news is full of El Nino today doesn’t necessarily mean prices will jump significantly higher just yet.

Nevertheless, we can agree that through the two year period there was significant interest followed by some disappointing northern hemisphere cane crops which definitely drove prices from 10c to 24c in the space of around a year.

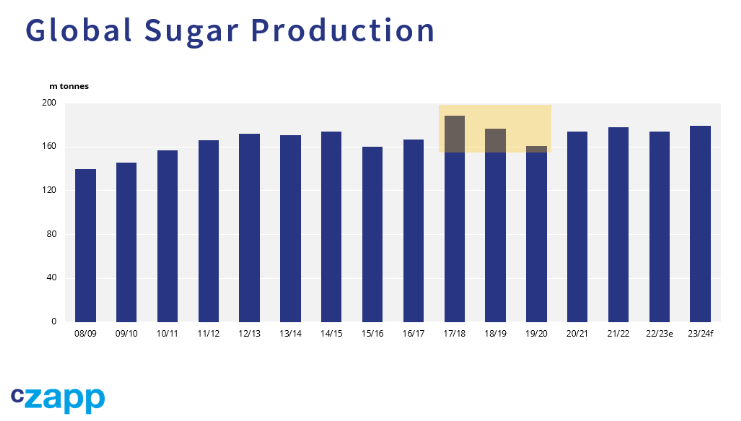

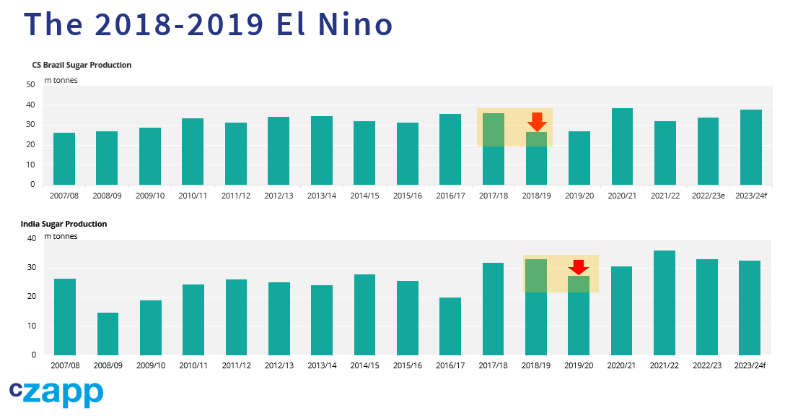

On paper the weak El Nino of 2018/19 also looks to have led to a major drop in global sugar production. However, these were also the years when CS Brazil swung from making ethanol and not sugar, diverting 10m tonnes of production each season.

The weather did lead to a fall in Australian, Thai, Indian and Pakistani sugar output, adding up to around 15m tonnes by 2019/20.

Here’s how prices looked from 2018 to 2020.

Perhaps prices had started to respond to this in September 2019, when they bottomed at below 11c then started to climb towards 16c.

We’ll never know, because the newsflow in 2020 was dominated by a new virus which spread around the world instead.

The final weak episode was a Central Pacific Modoki version in 2009/10

Global sugar production at the time was growing strongly from previous lows caused by India’s swing cycle, where farmers would plant excess cane in response to high prices, wouldn’t be paid on time for their huge crop and would then replant cane for other crops.

Any adverse impact on regional production was not noticeable in the global stats given the scale of India’s crop swings and Brazil’s cane growth.

It’s difficult to tell how much of the 2009-2011 bull market was due to El Nino. Some, perhaps but not all.

The sugar market had its own structural problems resulting from the reform of Europe’s sugar sector, meaning subsidized sugar supply was no longer available. Incidentally, you can see from this chart why so many analysts are concerned about the long term future for sugar prices.

So…the short version is that El Ninos are generally bad for northern hemisphere cane production in the west pacific and this might be a major story for the sugar market in the coming months.

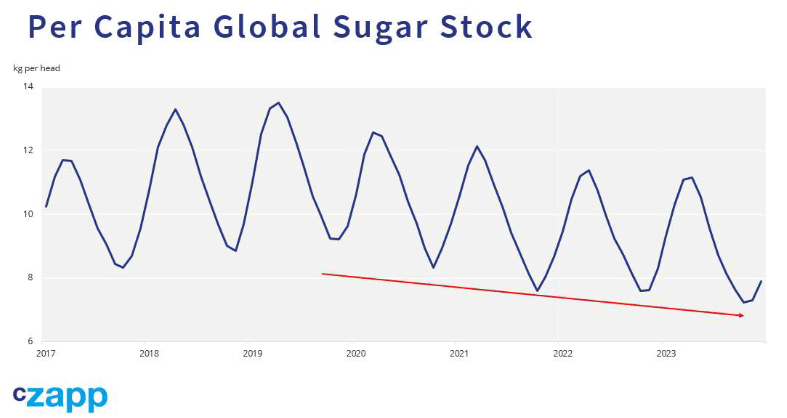

The world has run down sugar stocks and we are all badly placed to adapt to any crop shortfalls. This is why the market is so jumpy.

But El Nino is an unreliable bartender. We simply can’t say in advance what the impacts will be, how intense they’ll be or when they’ll happen.

All we can do is price in a risk premium into the futures markets, which is what seems to be happening today. If we get bad crop news in the short term – perhaps poor cane harvesting progress in Brazil or continued dryness in Thailand, the price will respond pretty quickly.

But if it takes time for the impacts to become clear, maybe I’ll get lucky and my previous assertion that there are no more sugar buyers left in the short term will still be correct.

For more articles, insight and price information on all things related related to food and beverages visit Czapp.