Insight Focus

COVID, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have put food security back into the spotlight. Governments build stocks, recognising the vulnerability of “just in time” supply chains. China leads the charge, but not everywhere can afford to do the same.

Increasing Sugar Stocks

The disruption to global supply chains caused by COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has refocused attention on food security.

For much of the 2000s, most supply chains have been operating according to “just in time” principles. After all, holding excessive stocks is expensive. But governments may now be calculating that the expense is worth paying if the alternative is hunger.

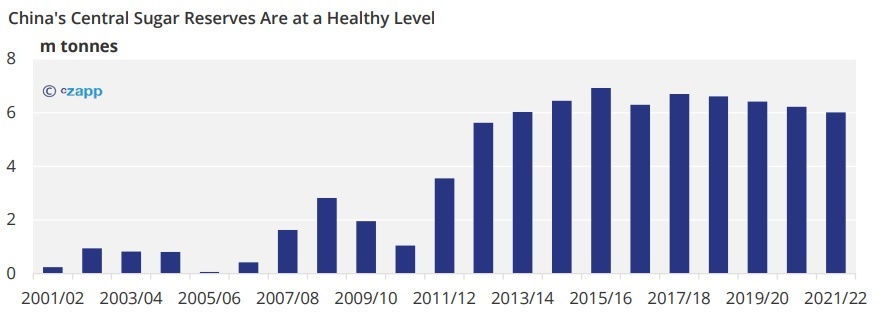

China has been a leader. Through the last decade, it has held large grains and sugar stocks. The government launched a ‘clean plate’ initiative aimed at reducing food waste pre-COVID, partly in response to the ‘trade war’ with the USA.

Other countries are catching on.

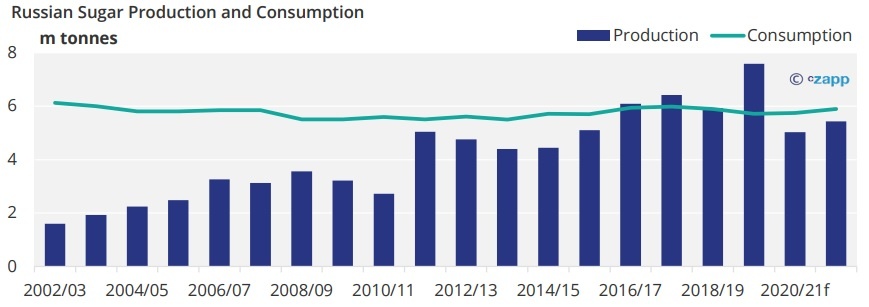

Russia is self-sufficient in food today. But its farming and food manufacturing sector still relies heavily on imports of higher technology equipment, whether it’s tractor spare parts or modern seeds. It’s possible that Russia’s self sufficiency starts to diminish if Western sanctions continue beyond 2022, or if adverse weather affects crop yields.

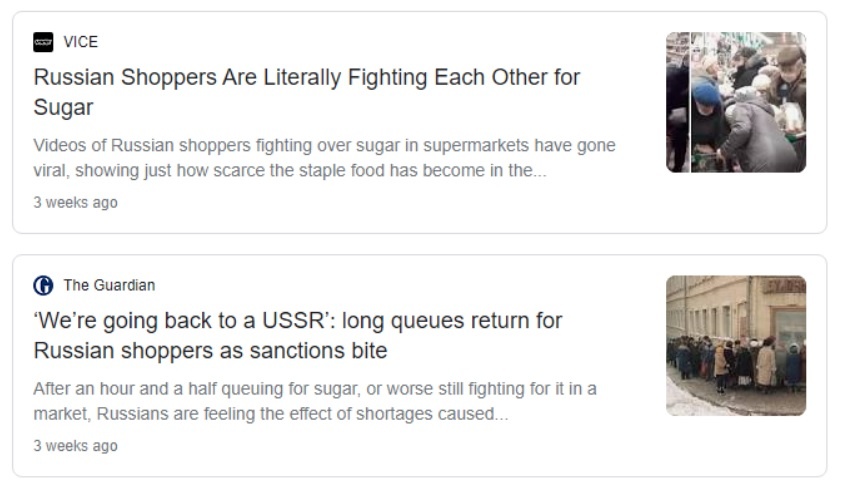

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russian consumers bought more basic foods than they normally would. This led to local stock-outs and higher prices, even if sugar stocks were sufficient at a national level.

To combat the possibility of local stock-outs in sugar, the government is creating security stocks. 250k tonnes will be stored at 16 locations around the country. This quantity is only two weeks’ consumption, but it enables to government to respond quickly to further supply chain disruption.

Other countries might not have similar concrete plans, but there’s no doubt we’ve seen some stronger-than expected sugar imports in some areas in recent months. This will translate to higher sugar stocks in the short term, boosting food security.

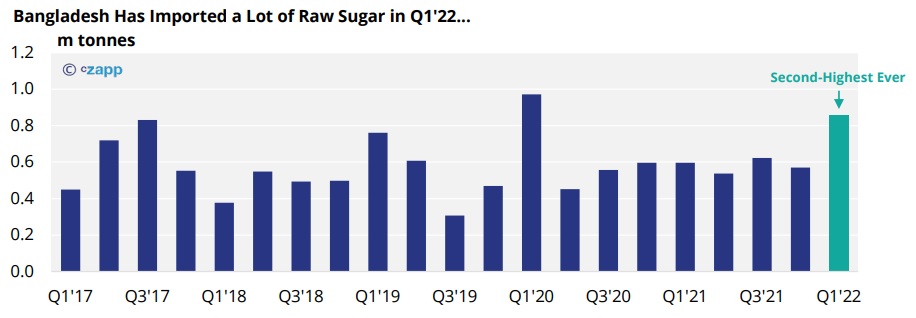

Bangladesh imported more than 800k tonnes raw sugar in Q1’22. This was because the government reduced the import duty from 30% to 20% to the end of February to reduce rising food prices.

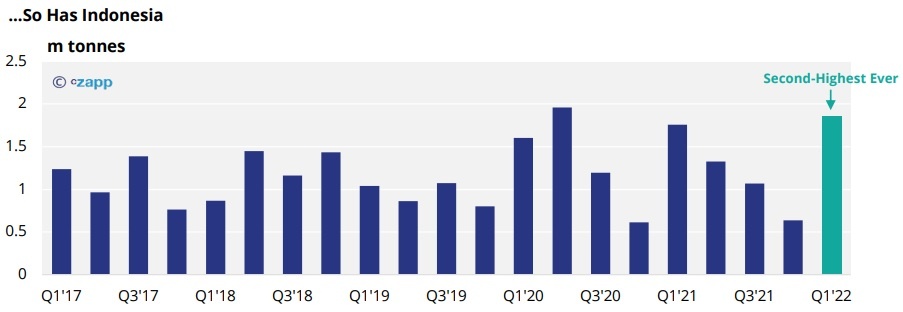

Look also at Indonesia, where raw sugar imports in Q1’22 have been close to record levels and there have been reported shortages of other foods like cooking oil and instant noodles.

Stress Elsewhere

At the other end of the scale, we also expect to see increased stress in some countries.

Sri Lanka informed creditors this week that it had become “challenging and impossible” to repay its external debt. It will instead save its FX reserves to import fuel and food. Protests have continued for more than a month over shortages of food and fuel, and FX reserves have fallen by more than 60% in two years. Sri Lanka has also started emergency talks with the International Monetary Fund.

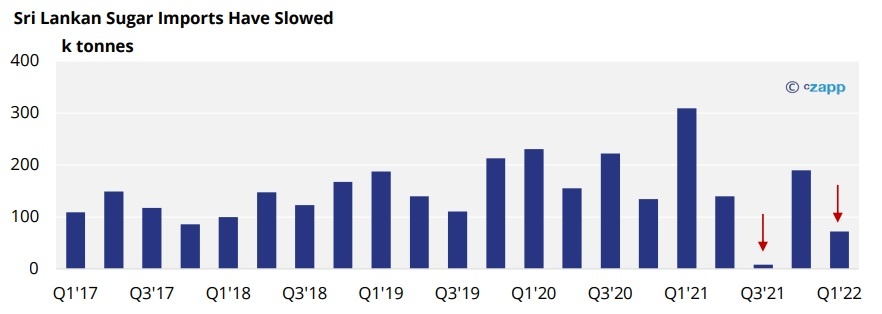

If we look at Sri Lankan sugar imports, we can see a pretty severe slowdown in arrivals.

Other countries are likely to arrive at a similar point to Sri Lanka. US Dollar availability has been low across a swathe of countries in recent years. Higher commodity prices could strain FX reserves further.

The problem isn’t confined to the Indian Ocean region. In Peru, rising fuel and food prices have led to weeks of protests and yields on Peruvian debt have climbed rapidly.

For countries without large food stocks (who also often happen to be those most exposed to food imports, and therefore higher prices), 2022 is turning into a difficult year. Although it was the COVID pandemic which first showed the importance of food resilience, 2020 also brought about multi-decade lows in commodity prices, and so the decision of whether to buy more food and fuel was a relatively easy one to make. Everyone likes to buy at low prices.

2022 is harder. Commodity prices are now close to multi-decade highs; do you buy what might be the top of the market to enhance food and fuel security? Perhaps yes if you’re China or Russia. But other countries might be tempted to wait to see if prices retreat.

After all, we may have already seen demand destruction in energy markets thanks to high prices: fertiliser plants coming offline thanks to high gas prices and people driving less/slower thanks to high gasoline prices. But food demand destruction is more problematic. It begins with people moving to cheaper foods: less meat, more grains. It ends with hunger.

For sugar, perhaps this means the bottom of the recent price range is more durable than we’d first assumed.

For more articles, insight and price information on all things related related to food and beverages visit Czapp.